Agoura Hills

Community History

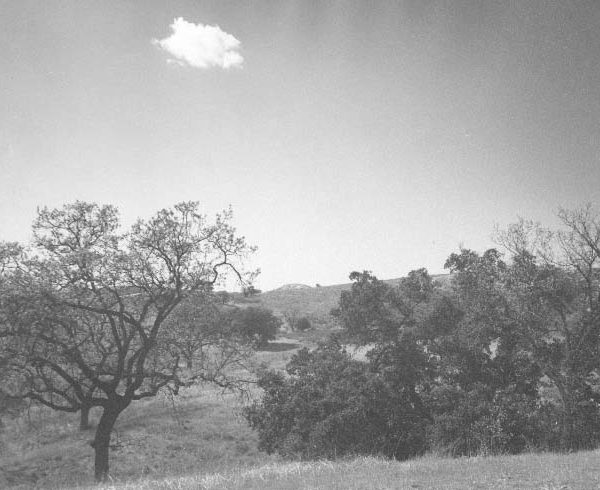

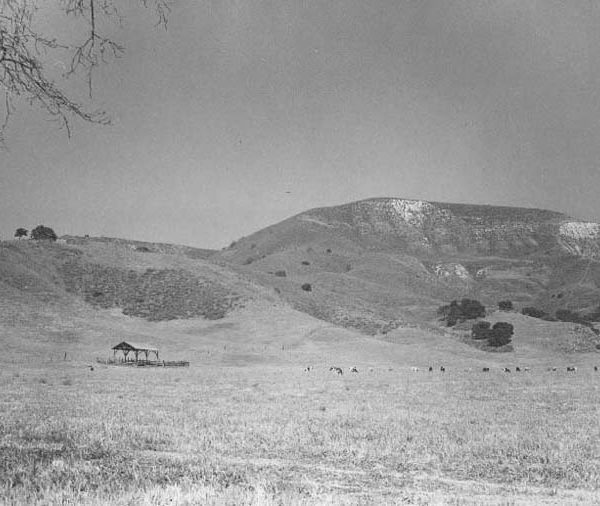

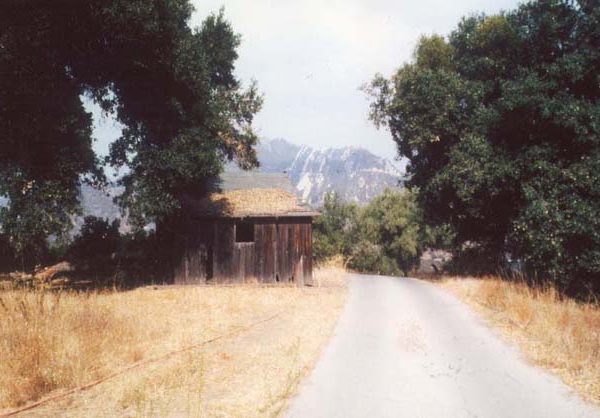

Perched on the western edge of Los Angeles County in the foothills of the Santa Monica Mountains, Agoura Hills is located just forty-five minutes from busy downtown Los Angeles, but is nevertheless rich with undulating hills and inspiring canyons. For many centuries the area that would become Agoura Hills was familiar territory for Native Americans who wandered inland from their haunts along the sea in search of game and other food. The permanent arrival of the Spanish in the late 1700s banished the Indians from their homes and introduced a ranching culture that would linger into the early twentieth century. In the 1900s, vast cattle and sheep ranches conceded ground to rows of lettuce and celery, orchards,and wheatfields. Ranching and agriculture eventually diminished in importance. Ranchers began dividing up their property and selling individual tracts for housing. From the outset, ranchers and farmers had worried about water supplies and these concerns were shared by the citizens of Agoura Hills into the mid 1950s. Then, provision of outside sources of water helped ensure the growth of the community, aided by the new highways which acted as a conduit for fresh faces and commercial development and contributed to the maturation of Agoura Hills.

Image Gallery

Frequently Asked Questions

In its earliest days, Agoura Hills was nothing more than a stagecoach stop and was referred to as “Vejar Junction.” In the early 1920s, after Paramount Studios purchased a ranch in the neighborhood, the community became known briefly as “Picture City.” But neither name stuck. In 1928, a group of residents formed a Chamber of Commerce which, as one of its first actions, asked to have a permanent post office established in the community. The Postal Department informed the chamber that it would need to submit a list of ten potential names for the town. One of the area’s more colorful early landowners had been a man by the name of Pierre Agoure. Though French by birth and a shepherd in his youth, he favored Spanish costumes and adopted the moniker Don Pedro Agoure. In compiling a list of possible names, the townspeople inserted “Agoure” in the tenth spot. Bob Boyd, the town’s first postmaster, later recalled that the tenth name was selected because it was the shortest. How the “e” became an “a” remains an unsettled issue. Some say it was done intentionally for ease of spelling, others lay blame at the door of the post office, arguing that the modification was simply an error.

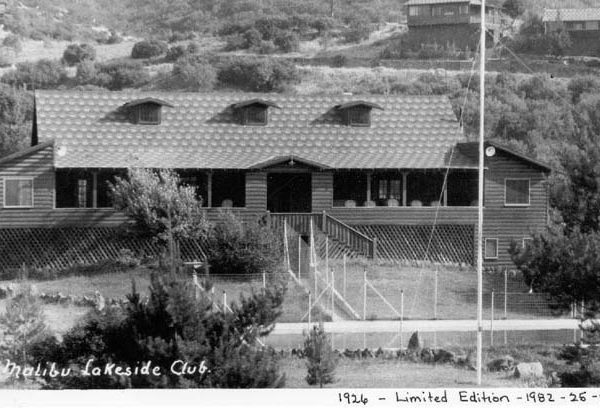

The “Malibou Lake Mountain Club” was incorporated in 1926 and in the following year purchased 182 acres in the Santa Monica Mountains. By 1928, the club had constructed a dam and a lodge for club members. The lake that formed behind the dam was used for recreational purposes. In addition, club members purchased lots on club property and erected vacation cabins there. Eventually, over 100 small houses and cabins stood on the property surrounded by oak, pine, sycamore, and acacia trees. Celebrities such as Clark Gable and Carole Lombard frequented the Malibu Lake community and club during its early decades.

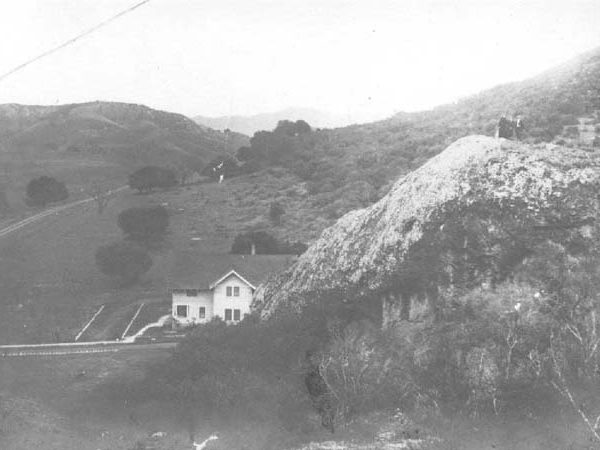

Built by early landowners Jose Reyes and Maria Altgracia Reyes de Vejar, the Reyes Adobe is located at 31400 Rainbow Crest Drive in Reyes Adobe Park. It was severely damaged during the Northridge earthquake in 1994 but has been restored to its original condition.

For many hundreds of years, Native Americans inhabited the land which would eventually become the city of Agoura Hills. Spanish explorers visited California briefly in the 1500s and 1600s, but it wasn’t until the late 1700s that Europeans arrived to stay. During a 1769 expedition from San Diego to Monterey, padre Juan Crespi wrote that the Agoura area was “a plain of considerable extent and much beauty, forested in all parts by live oaks with much pasture and water.” He called it El Triunfo del Dulcisimo Nombre de Jesus, or the Triumph of the Sweet Name of Jesus. Not long after, the Spanish set up 21 missions in California scattered from Los Angeles to San Francisco. El Camino Real (the “King’s Highway”) connected the different missions, tracing an old Chumash trail and bisecting the future Agoura Hills. At the missions, the Spanish did their best to turn the Chumash into good Europeans by attempting to eliminate their native culture. Through the introduction of new diseases and poor treatment, the Spanish also helped reduce their numbers.

Once in control of California, the Spanish king had begun granting land to his subjects. Miguel Ortega originally obtained a land grant for El Rancho de Nuestra Senora La Reina de Las Virgenes, or Rancho Las Virgenes, a tract comprising 17,760 acres in the vicinity of Agoura Hills. Later the land belonged to Doña Maria Antonia Machado del Reyes and her heirs Jose Reyes and Maria Altgracia Reyes de Vejar. The Frenchman Pierre Agoure first acquired property in the late 1800s and had title to nearly 17,000 acres “in and around Las Virgenes Rancho” by 1906. Like his neighbors in the early twentieth century, Agoure was a rancher, raising thousands of sheep and cows. Improved water pumping technology also led to increased agricultural endeavors in the Las Virgenes area, as farmers planted orchards, vegetables, and wheat.

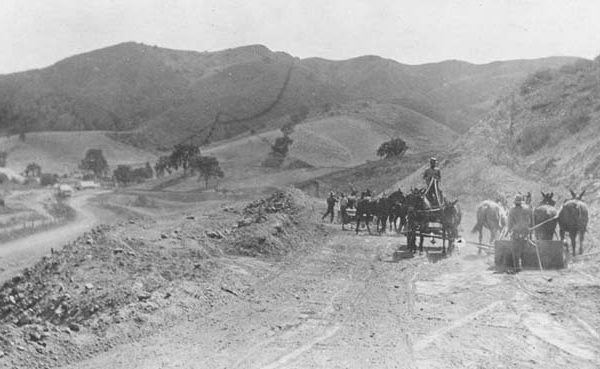

In the 1920s, a portion of the land near Agoura Hills was subdivided, dubbed “Independence Acres,” and advertised as a beautiful place for people to live where they could be independent and raise chickens. But water was scarce and many hopeful landowners eventually abandoned their independence and left. At about that time, Paramount Studios bought a ranch in the area (later known as Paramount Ranch) and it wasn’t long before the future Agoura Hills was being called “Picture City,” with movie makers latching on to it as a perfect backdrop for their films. In 1928, Picture City officially became Agoura Hills and in the succeeding decades the local population grew steadily. Water concerns lingered, however, and the issue of a permanent water supply was a continuous source of controversy in the community. In 1959, as the result of the hard work of a local citizen’s committee, the Las Virgenes Municipal Water District was established and Agoura Hills started bringing in water from the outside

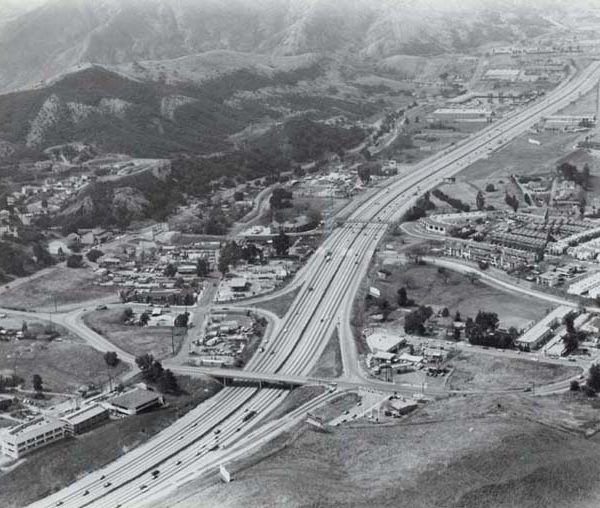

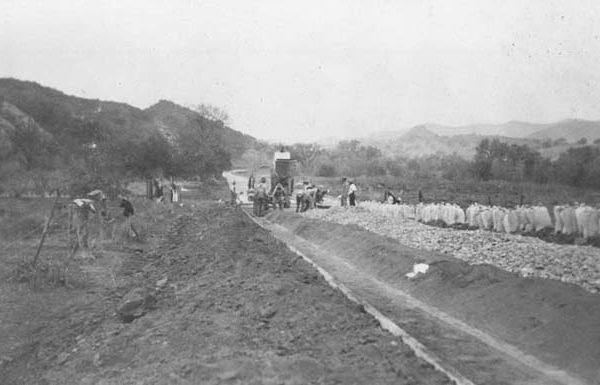

In 1963, the community began piping in water from the Colorado River. Reliable water sources made Agoura Hills more attractive for businesses and families. Furthermore, in 1956 another change had occurred which also dramatically influenced population growth and the character of the city: local highway 101 became the Ventura Freeway. Houses were soon sprouting throughout the area. During the late 1960s and 1970s, this speedy expansion continued, as housing tracts, shopping malls, and schools appeared in ever larger numbers. In 2000, Agoura Hills is a substantial suburb-its ranching industry long gone-and is home to roughly twenty times as many people as in 1950.

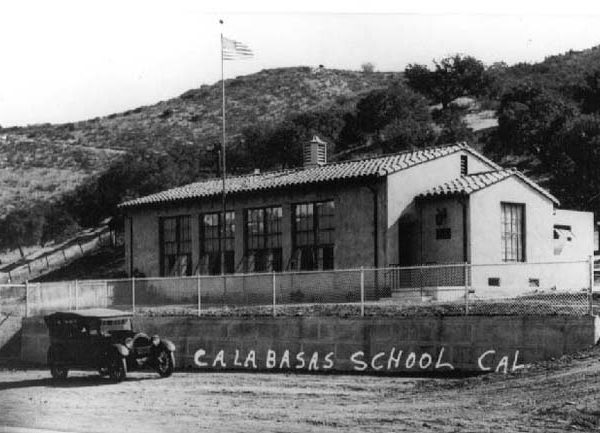

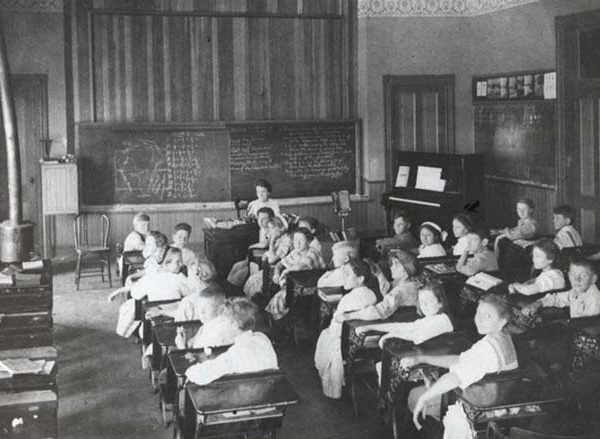

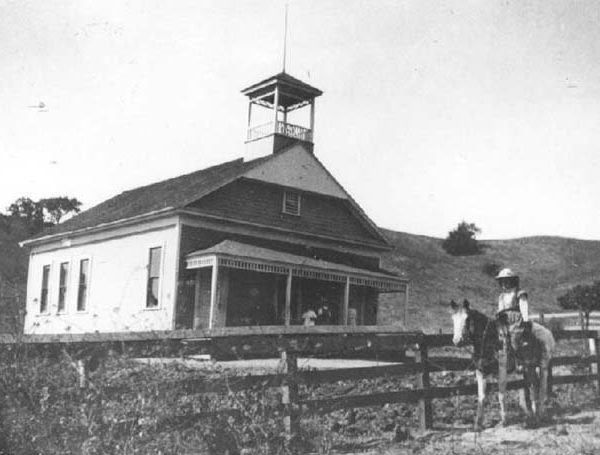

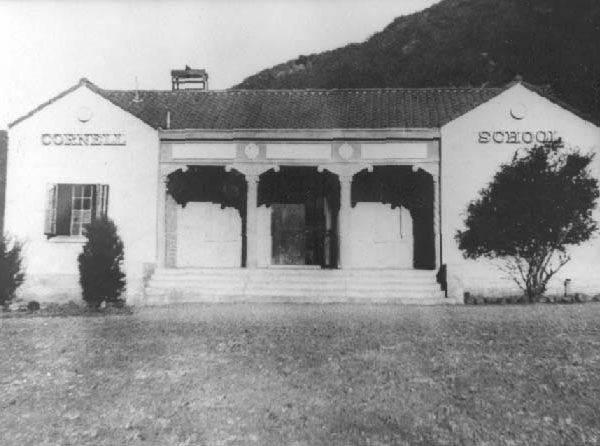

The Las Virgenes Unified School District was created out of four separate districts: Calabasas School District, Liberty School District, Cornell School District, and Las Virgenes School District. The four officially combined in 1947. In 1962, the district assumed its current name.

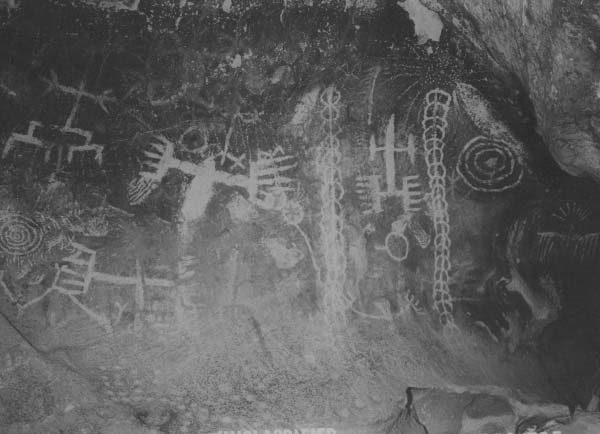

Hundreds of years ago, the area where Agoura Hills now lies was the home of the Chumash Indians. Inhabiting the Santa Barbara Channel Islands and territory in mainland California stretching from the western San Joaquin Valley to the Pacific coast and from Malibu Canyon to San Luis Obispo, the Chumash developed extensive trading networks, regularly exchanging supplies with their close neighbors as well as trading with Indians from further afield. They lived in circular, domed structures made with tule or reed thatch and poles. To survive, they ate seeds and lots of acorns, caught fish and other creatures from the sea, and hunted deer and antelope. Skillfully crafted plank boats provided the Chumash with vessels from which to capture food from the oceans and enabled them to journey to nearby islands for critical products such as soapstone (i.e., steatite)-obtained from quarries worked by the Gabrielino Indians of Catalina Island-which they used to make pipes, dishes, and decorative items. Few of the Chumash lived in the Agoura Hills area permanently, since year-round food supplies were much easier to come by near the shore. But each autumn some traveled inland and camped in the area while they collected acorns and hunted deer and rabbits.

When the Spanish arrived, they praised the Chumash as friendly and docile. The Spanish introduced their mission system in the late 1700s and set about converting and “civilizing” the Chumash. Some of the Chumash abandoned the coast for the mountains and inland valleys when the Spanish assumed control of California, but by the early 1800s most were part of the system. European diseases ravaged the local population of Indians, who were already suffering from the sometimes harsh treatment inflicted upon them by the Spanish, and by the mid 1830s their numbers had declined substantially. Following the secularization of the church lands in the 1830s, the Chumash were left to make their own way. Many ended up working for Mexican ranchers and, later, American settlers.

Learn more about the Chumash Indians

Chumash History

Original People of Los Angeles County

The Los Angeles Pierce College Beachy Library has many historical photographs of the Agoura Hills area. The Agoura Hills Library also has a small collection.

Beachy Library at Pierce College

6201 Winnetka Avenue

Woodland Hills, CA 91371

(818) 719-6410

In the 1800s, Spanish settlers established large ranches on the property they received from the King of Spain. Here they grazed vast herds of cows, slaughtering the cattle not for their meat, but for the hides and tallow that could be shipped to distant markets. Sheep, too, became a common sight on the ranches near present-day Agoura Hills. Even into the early twentieth century, ranching was the area’s dominant industry. In the 1900s, technology, including an improved water pump and the Stockton plow, also helped farmers to maintain prosperous orchards and fields of vegetables and grains. Nevertheless, the agricultural industry eventually declined. In at least one instance, a local rancher decided to subdivide his property and sell it off for housing when an epidemic of hoof and mouth disease decimated his livestock. Changes in the local infrastructure also attracted a different kind of resident after World War II, and by the end of the twentieth century Agoura Hills was a solidly suburban community.