San Fernando

Community History

San Fernando, the oldest city in the valley for which it is named, is located about twenty three miles north of Los Angeles, near the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains. Founded in 1874, it is nicknamed “The Mission City” because of its proximity to the San Fernando Mission that was established in 1797 and on whose former property the city emerged. San Fernando was originally populated by Gabrielino and Tataviam Indians, the latter naming the area “Achois Comihabit,” before Spanish explorers first passed through the region in 1769. In its pristine state, the hills and valleys were lush with oak and walnut trees. These gave way to ranches and farms in the nineteenth century, as an outgrowth of activities originally undertaken by the mission which thrived for nearly forty years during the early 1800s. During that time, while California was still Mexican territory, a mixture of Spanish, Indian, and Mexican residents arrived and settled in the valley. Following the mission’s secularization in 1834, it went into decline and was abandoned about a decade later.

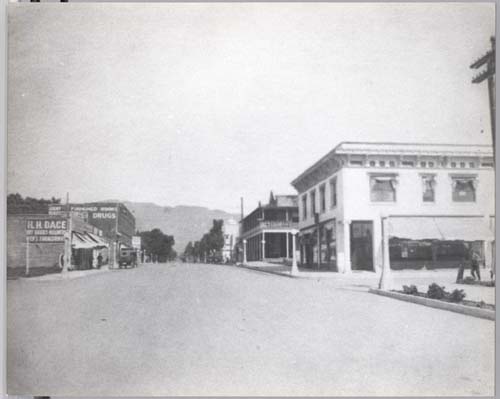

The city’s founding in 1874 was spurred by a land boom in Southern California and the Southern Pacific Railroad’s building of a rail line between Bakersfield and Los Angeles through Fremont Pass. Soon populated with an influx of settlers, San Fernando became known as the railroad’s “gateway to the north,” and with its Mediterranean climate and deep wells that provided water for irrigation, the community cultivated an abundance of vegetables and fruits, especially citrus and olives. That independent water supply allowed San Fernando to remain autonomous and incorporate in 1911, while most of the valley’s other communities felt compelled to annex to Los Angeles in 1915 to avail themselves of the waters of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, which started flowing in 1913. Today, with a population of about 22,600 people, San Fernando is one of the valley’s smaller communities but has retained its individuality and identity with an annual fiesta in celebration of its mission days and downtown architecture that reflects the city’s longtime Mexican heritage.

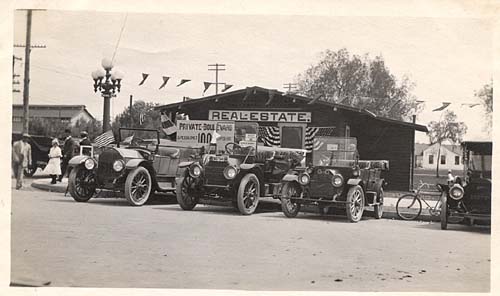

Image Gallery

Frequently Asked Questions

San Fernando was named after the valley in which it is located, “El Valle de San Fernando.” The valley was named by the founders of the San Fernando Mission. The mission, the seventeenth to be established in California, was named in honor of King Ferdinand III, the thirteenth king of Castile and Leon in Spain. For almost a decade before the mission was established in 1797, Spanish explorers who first came through the area called the valley “El Valle de Santa Catalina de Bononia de los Encinos,” which means The Valley of St. Catherine of Bononia of the Live Oaks. Prior to the arrival of white explorers, the native Tataviam Indians called the area Achois Comihabit.

San Fernando’s first inhabitants were Gabrielino and Tataviam Indians. The first Spanish explorers came through the valley in 1769, led by Gaspar de Portolá on an expedition from San Diego to Monterey the same year that Spain first occupied California. Though a priest named Francisco Garcés crossed the upper part of the valley in 1776, the area near what is now San Fernando really became settled after a party in 1797 went in search of a new mission on the way to the San Gabriel Mission. They chose a site that Tataviam Indians called Achois Comihabit and that was being run as a ranch by Francisco Reyes, who gave up his interest in the property so the newcomers – Franciscan clergy – could start the San Fernando Mission, the seventeenth mission in the state of California.

The missionaries were drawn to the location because of its fertile soil, abundant spring water for irrigation and drinking, pine longs and limestone from the San Gabriel Mountains for building materials, and a Native American population that could be converted to Christianity and used for labor. Mission founders held their first baptismal ceremonies September 8, 1797, and soon set up a vast irrigation network and trained Native Americans in many trades and skills, as well as farming and ranching techniques. By the early 1800s, the mission had become a small but thriving center of trade where Native Americans bought and sold fruits, vegetables, olives, wine, and livestock. The mission flourished for nearly forty years, until a move during 1830s to secularize California’s missions shifted their administration from Church to lay people. That change took place at the San Fernando Mission in 1834 when Don Pedro Lopez was appointed mayordomo, the civil administrator in charge of agricultural operations. The mission went into decline even as gold prospectors and settlers started arriving after gold was discovered in 1842 in nearby Placerita Canyon, and it was abandoned around 1845.

In the 1860s Lopez’s daughter, Catalina, and her husband Geronimo settled on about forty acres north of the mission and started the first non-religious settlement in what would soon become the community of San Fernando, building a school, post office, stagecoach stop, and home.

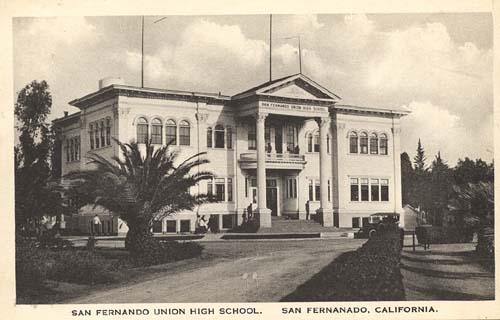

The following decade, swept up in a land boom in Southern California, a group of investors in 1874 bought property along a railway line that the Southern Pacific Railway was building, started subdividing the land into plots, and brought in prospective property owners from Los Angeles. One of the investors, Senator Charles Maclay, called the new community San Fernando. It was the first city in the San Fernando Valley and was nicknamed “The Mission City.”

San Fernando was founded in 1874 and grew into a community renowned for its fruits and vegetables, especially citrus and olives. One of the reasons for its plentiful production of crops was a reliable water supply from several deep wells, which had originally fed the mission’s irrigation systems and that allowed San Fernando to maintain its municipal independence as adjacent communities struggled to find sufficient water to irrigate their crops. After the 250-mile Los Angeles Aqueduct opened in 1913, bringing the waters of the Owens Valley to residents of Los Angeles, many San Fernando Valley communities annexed to Los Angeles in order to receive fixed water rates. Their collective rush to annex was prompted by a campaign whose rallying cry was “Put the Aqueduct Water to Work at Once.” San Fernando’s autonomy has made the city what one writer called “an island in a sea of suburban Los Angeles.”

Photographs are available from the San Fernando Valley Historical Society and the Security Pacific Photograph Collection at the Los Angeles Public Library.

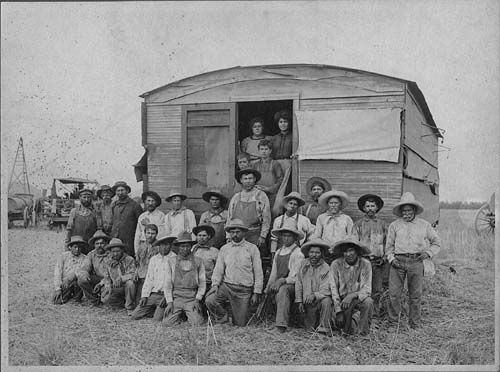

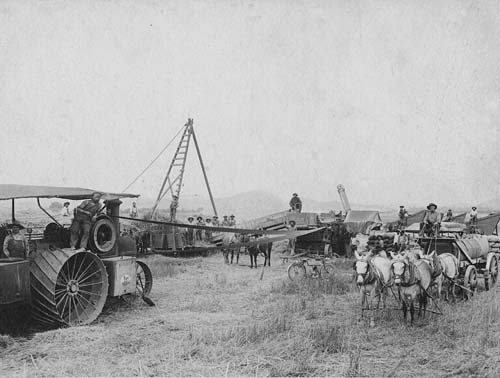

For about a half century between San Fernando’s 1874 founding and the 1920s, the community was considered an “agricultural gem” set in the San Fernando Valley, thanks to a double blessing. An ample and reliable water supply was coupled with a coastal valley climate, in which the community’s elevation of about 1,100 feet – along with its receiving about 12 inches of rain a year – made it ideal for growing crops. Though cattle ranching was common in the area when missionaries arrived in the late 1700s, by a century later the landscape was dotted with wheat plantings and fruit trees, whose growth was also aided by the irrigation systems in place from the Mission’s heyday.

By the 1920s, with further assistance from the waters of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, fruit and especially citrus cultivation was San Fernando’s biggest industry. The price of land for orange and lemon groves went as high as $5,000 an acre – as much as eight times more than the cost of other land – and the city had at least four packing houses with annual shipments of nearly 500 rail cars of oranges and lemons. Olives also flourished in the Mediterranean-like climate, and the 2,000-acre Sylmar olive grove – then the world’s largest – produced 50,000 gallons of olive oil and 200,000 gallons of ripe olives. Other crops grown in and around San Fernando included alfalfa, apricots, asparagus, barley hay, beans, beets, cabbage, citrus, corn, lettuce, melons, peaches, potatoes, pumpkins, squash, tomatoes, and walnuts. The area also had excellent dairy farms including during the 1920s the world’s largest Guernsey herd. San Fernando’s agricultural output led to other industries such as canning companies, a fruit growers’ association, and fruit preservers. Like most other communities in Southern California, San Fernando’s agricultural land gave way to development following World War II.

San Fernando became a community as a result of the juxtaposition of Southern California’s land boom during the 1870s and the Southern Pacific Railroad’s construction of a rail line, during that same decade, between Los Angeles and Bakersfield through Fremont Pass. The rail line’s construction began at either end and was to be connected with a nearly 7,000-foot tunnel near the pass. When the southern piece of the line was completed – with Southern Pacific rail service between Los Angeles and San Fernando starting on January 21, 1874 – San Fernando became the rail line’s northern endpoint until the tunnel was completed. Meanwhile, inspired by the prospect of train travel through the area and land-hungry property owners, Northern California investors bought land from the now-defunct San Fernando Mission and in 1874 began subdividing the property next to the railroad’s path into streets and plots.

The 1876 completion of the line, thus linking both ends of California, opened up San Fernando to a growing population and business base and markets for its agriculture. Over the next two years, railroad officials brought possible residents from Los Angeles to the new town and soon the town had a bustling downtown and general store and was shipping agricultural products via railroad. Later daily trains on the Pacific Electric Railway came through as well. By the 1920s, San Fernando was considered “the gateway to the north” on the Southern Pacific’s main line.

The Mission San Fernando Rey de España was founded on September 8, 1797, by Father Fermin Lasuen, a Basque priest who was following in the footsteps of the pioneering Franciscan missionary, Father Junípero Serra. The San Fernando Mission was the seventeenth in a succession of twenty-one missions established in the state. It consisted of an extensive compound of buildings, including a large church made of adobe brick and tile. The mission flourished from the start, as a small group of Franciscan friars taught local Native Americans a variety of skills that earned the mission a solid reputation for its farming, cattle-ranching, carpentry, ironwork, leatherwork, weaving, and vineyards and orchards that produced brandy and wine.

The San Fernando Mission became one of the most thriving and prosperous in the state of California. By 1819 it had nearly 15,000 cattle, sheep, and horses, and a multitude of buildings in its adobe compound, including a convent, cemetery, 20-room residence building, chapel, kitchen, and workshop buildings. During the period that lasted into the 1830s, thousands of Native Americans were baptized, and many of them were also buried behind the mission church in the cemetery. Church attendance was so great that between the mission’s founding and 1804, the first church on the site was replaced by two more, each larger than the preceding one. Keeping watch over the altar was the original statue of the canonized King Ferdinand III of Spain, the mission’s namesake.

However, following the Mexican revolt from Spain, between 1834 and 1836 California officials secularized the missions and confiscated property. During these years, most of the Native Americans at the San Fernando Mission were evicted. A mayordomo named Don Pedro Lopez was put in charge of agriculture, but the mission quickly declined, its downhill spiral compounded by a rapid decrease in the Native American population. The mission’s buildings crumbled and became vermin-infested; its bells, books, furniture, vestments, and stations of the cross were looted; and in 1845 its buildings were almost entirely abandoned. The property passed into private hands and was subdivided several times over, and for close to a century a number of individuals and groups tried unsuccessfully to save the mission from utter ruin. These would-be attempts included those by Charles Lummis and the Landmarks Club in 1897, a “Candle Day” in 1916 intended to sell enough candles at a dollar each to pay for a new church roof, and an exiled Mexican bishop’s failed efforts to start a boys’ school.

In the 1930s, however, Southwest Museum curator M.R. Harrington established the Friends of the Mission, who began restoration with the help of other organizations and groups that included the Native Daughters of the Golden West and the Women’s Auxiliary of the Los Angeles Chapter. The refurbished site was rededicated in 1941, and after World War II the William Randolph Hearst Foundation set up a Mission Restoration Fund. A devastating earthquake in 1971 again damaged the mission’s buildings, including the church, but these structures were rebuilt or repaired as needed. Today the mission located just two miles away from San Fernando is a major tourist attraction.

Before white explorers from Europe came through the area, the region where San Fernando is now was inhabited by Gabrielino and Tataviam Native Americans, the latter calling the area Achois Comihabit. The Gabrielinos arrived around 500 B.C. as part of the so-called Shoshonean wedge. In the San Fernando Valley, the Gabrielinos – one of the wealthiest and most powerful groups in southern California before the arrival of Europeans – spoke a dialect called Fernandeño. They occupied the general area that included the Los Angeles, San Gabriel, and Santa Ana river watersheds, and those of smaller streams in the Santa Monica and Santa Ana mountains; the Los Angeles basin; coastal lands between Aliso and Topango creeks; and San Clemente, San Nicolas, and Santa Catalina islands. Living in villages of between 50 and 100 people, Gabrielinos were known for being spiritual, brave, and peaceful. Their culture declined quickly with the establishment of the San Gabriel Mission in the early 1770s, after Spanish explorer Gaspar de Portolá entered their territory while crossing California in 1769.

When Franciscan fathers arrived to establish the San Fernando Mission in the 1790s, local Native Americans were helping Francisco Reyes run his ranch, called the Reyes Rancho, whose property he then gave over to the mission. Soon the missionaries had cast a wide net across the valley, baptizing Indians who were Cahuenga, Camulos, Piru, Simi, Topanga, and Tujunga, from almost 200 rancherías (villages). At the mission, hundreds of Indians lived there while priests taught them to farm, raise and care for animals, cure hides, work in vineyards and make wine, and trades including carpentry, masonry, tailoring, shoemaking.

In the early 1860s, Geronimo and Catalina Lopez – the daughter of majordomo Pedro Lopez – bought about forty acres of land north of where the San Fernando Mission had been. They built a big adobe home and stagehouse known as Lopez Station. They made their mark in the area, with Don Geronimo opening the first post office in the valley in 1869 and also starting its first general store at Lopez Station. Their Lopez Adobe home was built by Valentin Lopez, Geronimo’s cousin and brother-in-law, in 1882-83 at what is now the corner of Maclay Avenue and Pico Street. The Lopezes represented a bridge between the Mission’s former glory days and the 1874 founding of San Fernando as its own community, with gold rush fever and an influx of settlers filling the intervening years. In the process, they witnessed the area’s evolution from ranching to agriculture to orchards to development. Their Lopez Adobe home was the first two-story adobe residential structure in the San Fernando Valley, and to this day it is considered the city’s oldest standing building. The 1997 bicentennial of the mission coincided with the restoration of their home, which was damaged in the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

Water from the Owens Valley, which was transported 250 miles to Los Angeles via the aqueduct starting in 1913, allowed the San Fernando Valley which had been a dry-farming region largely dependent on rain for agriculture to flourish as an agricultural community. The Owens River drained snowmelt from the Sierra Nevadas. In around 1900, residents of the Owens Valley hoped that with passage of the National Reclamation Act they could channel the river into irrigation projects for their own agricultural uses. Instead, Los Angeles officials acquired the water rights to the Owens River by purchasing the surrounding land. In 1907, Los Angeles residents approved $23 million in bonds to pay for construction of the aqueduct, known variously as the Los Angeles Aqueduct and the Owens Valley Aqueduct. Construction began the following year, and on November 5, 1913, the gates of the aqueduct opened at “The Cascades” northwest of San Fernando and brought the river water to the growing city of Los Angeles.

Completion of the aqueduct – at the time the country’s largest municipal water system – transformed San Fernando and the San Fernando Valley. It led, among other things, to long-range planning for development and the formation in 1909 of The Los Angeles Suburban Homes Company. Part of Lopez Station is today covered by a reservoir now owned by the city of Los Angeles. Chatsworth, near San Fernando, was formerly called “Owensmouth” because it was where the Aqueduct entered Los Angeles County.

Richard Steve Valenzuela, aka “Ritchie Valens,” was the so-called father of Latin and Chicano rock music, who died February 3, 1958 at the age of seventeen in an airplane crash. He grew up in San Fernando and attended the city’s schools and became known for his hit song “La Bamba” while establishing himself as one of the biggest pop music phenomenons of his time. The Mexican-American Valens used pioneering music techniques of combining rock and jazz and using a medley of melodies within his songs, and made his brief but memorable mark on music with three albums in less than eight months. When he was born in 1941, his parents lived at 1337 Coronel Street in San Fernando; they separated when he was three years old and Ritchie often stayed with his father, who now lived in Pacoima. His father died in 1951 when Ritchie was 10, and the boy went on to live with various extended relatives, several of whom exposed him to music.