Willowbrook

Community History

Willows and a slow, shallow brook distinguished this portion of the Los Angeles plain long before it was given the name “Willowbrook.” A lone-standing streamside willow tree near the present intersection of 125th Street and Mona Boulevard was an original rancho boundary marker in the 1840s. Willowbrook was probably named after the willows that grew around the many springs that watered the area prior to extensive agricultural and suburban development, beginning in the late 1800s. In earlier years, the land that is now Willowbrook was part of the 4,500 acre Rancho Tajauta, granted to Anastacio Abila in 1843.

The first subdivisions in the Willowbrook area were filed in 1894 and 1895 and the first official use of the name Willowbrook came in 1903, when the Willowbrook Tract was recorded with the County Recorder. The deep lots in the Willowbrook subdivision enabled residents to grow fruits and vegetables, run hogs, and raise chickens behind their homes. This mixture of suburban and rural land uses continued in Willowbrook into the early 1980s. At that point, Willowbrook began to lose its rural character due to redevelopment that introduced an increasing number of new commercial and residential facilities into the area. As a result, present-day Willowbrook appears similar to other communities in the South Central section of Los Angeles.

Image Gallery

Frequently Asked Questions

Madame A C Bilbrew (1888-1992) was a community leader and a former deputy to Los Angeles County Supervisor, Kenneth Hahn. She was also known world-wide for her versatility as a musician and poet. She was a producer of pageants and dramas, an outstanding dramatic reader, and a choral director. She received national and international recognition for her performances on the stage and in film. Despite her busy schedule, Madame Bilbrew gave freely of her time and talents to the Willowbrook community, particularly in efforts directed toward better understanding among youth.

Madame Bilbrew was born in Washington, Arkansas in 1888, as the seventh of ten children of the Reverend S. L. and Rebecca Harris. She attended Texas College in Tyler, Texas and studied piano at the University of Southern California School of Music. She later married A. C. Bilbrew and became the mother of three daughters.

In 1923, Madame Bilbrew was the first Black soloist to appear on radio. In 1940 to 1942, she directed and announced the “Gold Hour” which aired over Radio Station KGFJ. In 1960, she was a delegate to the Women’s Convention in Copenhagen, Denmark, and was chosen by the “Women of the Soviet Union” to visit Russia. In 1961, she was elected Chairman of the Fine Arts Department of the National Council of Negro Women and founded the “Opportunity Workshop” for cultural development of youths and adults for the Willowbrook community in 1963. Madame Bilbrew directed the Senior Choir of Phillips Temple C.M.E. Church for a number of years, became director of the Radio Choir of Peoples Independent Church of Christ, and directed the Radio Choir of Hamilton Methodist Church. When the present library building was opened in November of 1974, it was named in her honor.

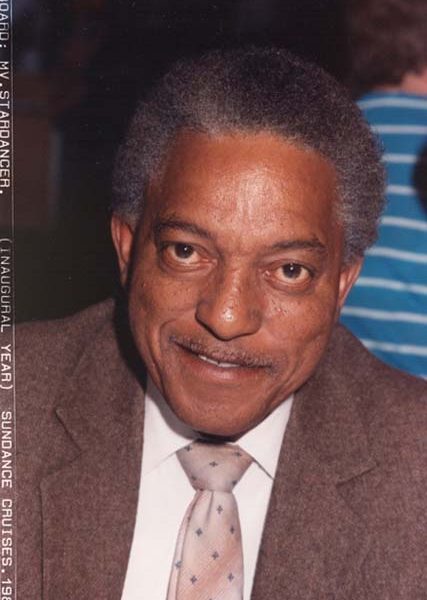

Vincent Proby, the architect of the A C Bilbrew Library and numerous other public and private buildings, was born in Wichita, Texas. He moved with his family to Los Angeles at a very early age and attended Los Angeles Public schools, Los Angeles Junior College, and the University of Southern California, where he majored in architecture.

In the first years of his architectural career, he served as project manager for many prominent buildings, among which were the Los Angeles Sports Arena and the Las Vegas Airport, eventually founding his own firm. He designed many projects in the state of California, including several buildings for the Los Angeles Unified School District, several on the UCLA campus, and Los Angeles City College, Pierce College, and Scripps Institute. His projects also included banks, libraries, museums, medical buildings, churches, mortuaries, private residences, children’s centers, shopping centers, and military buildings.

Proby was the first member of a minority group ever appointed to the State Board of Architectural Examiners, where he served for eight years. During that period, he was elected and served the organization as Secretary, Vice-President, and President. He also served on a number of different committees for the National Board of Architectural Examiners and assisted in writing the National and California architectural examinations. He served as an examination grader for ten years. In addition to his distinguished architectural career, he also held the California Teaching Credential and served for many years as a guest teacher for several state and private universities.

Native Americans who lived in the Los Angeles area spoke a language distinct from their neighbors to the North and South of them. They have come to be known as Gabrielinos, because many of those who survived European diseases and the disruption of their normal trade patterns and culture went to the Mission San Gabriel, some voluntarily, others only when confronted by force. The Gabrielino lived in domed, circular structures with thatched exteriors. Both men and women wore their hair long and used a vegetable charcoal dye and thorns of flint slivers to tattoo their bodies. They required very few clothes, though women usually donned deerskin or bark aprons, and all might wear animal skin capes in cold or wet weather. Like most California Indians, the Gabrielino of the South Gate area ate roots and berries, rabbits, antelope, squirrels, crows, and other birds.

The first European to visit the future home of South Gate discovered many Indian villages between the Pacific Ocean and the San Gabriel mountains. Two villages, probably known as Tibahag-Na and Ahau, are thought to have been located within the boundaries of the present community. Passing through during the mid 1700s as part of Spaniard Gaspar de Portola’s famous expedition from San Diego to Monterey, Padre Juan Crespi observed that the Indians in the area were very friendly. Nevertheless, during the late 1700s and early 1800s, after dominating the Los Angeles basin area for hundreds of years, those Gabrielino who did not flee were gradually moved to Spanish missions. Many became laborers for local landowners. Most eventually adopted a new, more European lifestyle. By the twentieth century, few traces of Gabrielino culture remained.

Willows and a slow, shallow brook distinguished this portion of the Los Angeles plain long before it was given the name “Willowbrook.” A lone-standing streamside willow tree near the present intersection of 125th Street and Mona Boulevard was an original rancho boundary marker in the 1840s.

Willowbrook was rich in springs in the early days and winter rains would bring up fine stands of rye grass between gravelly ridges left by long-ago floods of the Los Angeles River. As early as 1820, Don Anastacio Abila was grazing cattle on the land and by 1843, the Mexican governor had granted him 4,500 acres. This grant was named the Rancho Tajauta and it extended from the marshes along present Alameda Street westward to approximately the present line of the Harbor Freeway. All of present-day Willowbrook is within the area covered by Rancho Tajauta.

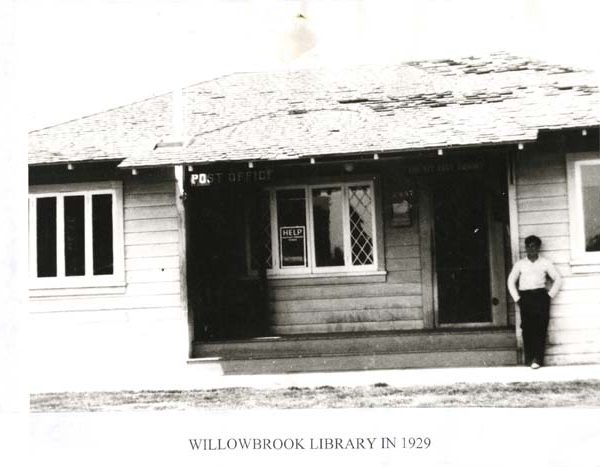

The first subdivisions in the Willowbrook area were filed in 1894 and 1895 on land along what is now Rosecrans Boulevard. The first official use of the name Willowbrook came in 1903, when the Willowbrook Tract was recorded with the County Recorder. The tract straddled the newly opened Pacific Electric railway line to Long Beach. There is no evidence that a townsite was envisioned and street patterns were not coordinated with adjacent tracts. The name Willowbrook came into use for the whole area, because the Big Red Cars of the Pacific Electric Railroad Company stopped at 126th Street in Willowbrook.

Lot buyers in Willowbrook expected to live a definitely suburban life. The deep lots (up to 300 feet deep in many cases) attracted working-class families, especially newcomers to Southern California. The Big Red Cars provided fast, reasonable transportation to department stores in downtown Los Angeles and to jobs in the Long Beach and San Pedro harbor areas. During the Depression years, residents used the land behind their homes to grow fruits and vegetables, run hogs, and raise chickens. These land uses, together with the vacant lots covered with mustard plants, intensified the area’s rural appearance. After the end of the Depression and World War II, increasing suburban development occurred in Willowbrook, but not to the extent that it substantially altered the area’s rural character. Even the 1965 Watts Riots did not change that, although Willowbrook suffered damage to a number of its buildings, including Willowbrook’s community library.

The mixture of suburban and rural land uses continued in Willowbrook into the early 1980s, when the area began to lose its rural character due to a redevelopment plan drafted by the Watts Labor Community Action Committee (WLCAC) under the leadership of Ted Watkins and supported by Los Angeles County. Under this plan, 365 acres of Willowbrook land was redeveloped to provide new commercial and residential facilities. As a result, present-day Willowbrook appears similar to other communities in the South Central section of Los Angeles.

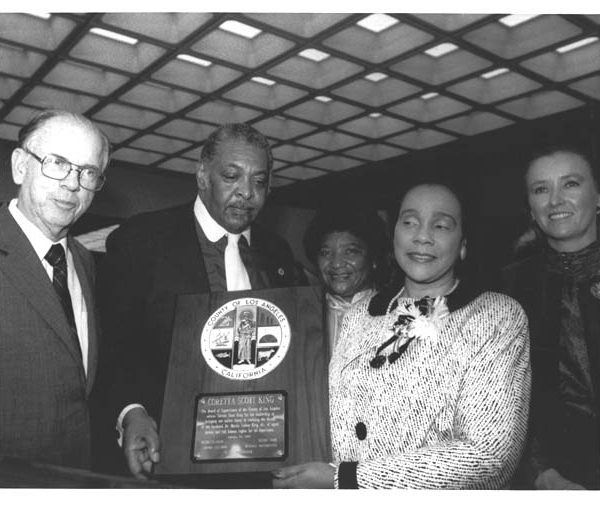

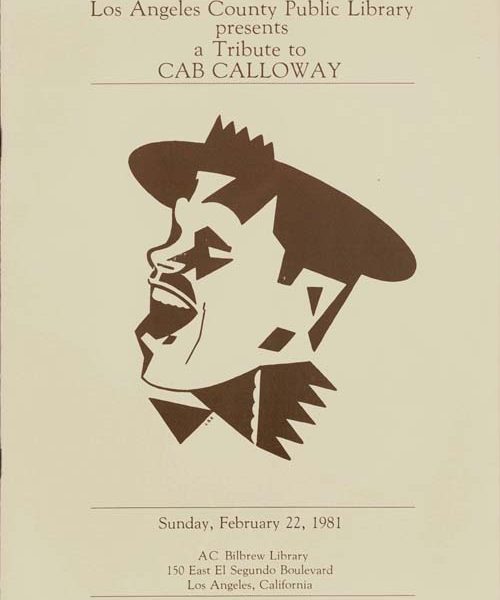

Since 1980, the A C Bilbrew library has hosted the County Library’s African American History Month Celebration. Eubie Blake was the first honoree of the “Living Black History Tribute” (later the “African-American Living Legend” series), a focus of the Library’s celebration. Other honorees have included Cab Calloway, Count Basie, Rosa Parks, James Baldwin, Coretta Scott King, and Ray Charles.

Prior to the 1950s, when deed restrictions and zoning codes limited where African-Americans could live or operate businesses, Central Avenue to the south of downtown Los Angeles served as the focus of the African-American community’s residential, economic, and cultural development. Jazz found a particular home here from the 1920s to the 1950s. The Hotel Dunbar was the area’s best known venue for Black jazz performers, including Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, and Louis Armstrong.