Claremont

Community History

Located at the base of the San Gabriel Mountains along the eastern rim of Los Angeles County, Claremont has been called by some “a bit of New England with a sombrero.” For hundreds of years, Serrano Indians made their homes on its soil, only to be driven out by the Spanish missionaries, Mexican ranchers, and American settlers who put down roots there during the 1800s. The arrival of the railroad late in the century signaled the eventual departure of grazing cattle and herds of sheep meandering through clumps of sagebrush. Land developers invented Claremont in the 1880s, assuming the need for a town at its specific location along the gleaming tracks of the Santa Fe Railroad’s newly opened Chicago to Los Angeles route.

A real estate bust threatened the town’s future, but also led to the relocation of Pomona College to the unused Claremont Hotel. With a handful of professors committed to the college and its community, Claremont grew stronger. A blossoming citrus industry provided additional inhabitants and income and the town would eventually benefit from its role as a station on a passenger rail line heading into Los Angeles. As the twentieth century reached middle age, the railway shut down and the citrus groves gradually vanished. But Pomona College gave birth to five sister colleges during the 1900s, further solidifying the educational focus of the community, and Claremont grew larger and more populous after World War II, helped by new highways and industrial and residential growth in the greater Los Angeles area.

Image Gallery

Frequently Asked Questions

Nomadic Native Americans first inhabited the area which would eventually become the city of Claremont. In 1769 Spanish explorers traversed Southern California from San Diego to Monterey and in 1771 the Catholic Church established the Mission San Gabriel, with lands extending from San Pedro Bay to the San Bernardino Mountains. Some fifty years later, Spain relinquished California to newly independent Mexico, and in 1834, the Mexican state secularized all church lands.

Ygnacio Palomares and Ricardo Vejar, who were raising their many horses and cattle in crowded Los Angeles, eyed the now vacant mission lands and in 1837 applied to the governor of California for a grant of land in the area “known by the name of San Josi.” The governor approved their request and the two (later joined by Palomares’ brother-in-law Luis Arenas) moved to Rancho San Josi, constructing adobe homes, planting vegetables, and grazing their cattle and sheep near present-day Claremont. Their families remained in the vicinity for many years, retaining title to the lands even after the United States annexed California in 1848. The first American to take up permanent residence close by was W.T. “Tooch” Martin, who purchased 156 acres near the mesa now called Indian Hill in 1871.

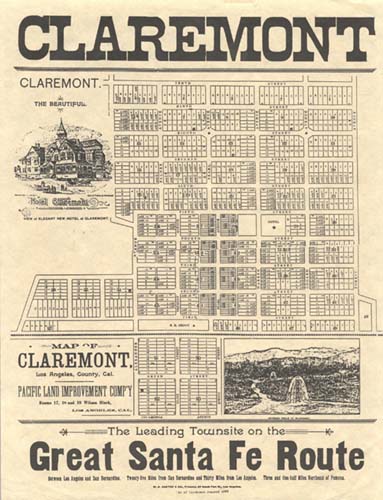

By the late 1880s, larger numbers of American settlers were migrating westward, assisted by expanding railroads. In 1887, the Santa Fe Railroad Company finished the San Bernardino to Los Angeles section of its Chicago to Los Angeles line. Expecting a population explosion, land developers mapped out about thirty town sites along that stretch of the rail line. The Pacific Land Improvement Company bought 365 acres and staked out plots to sell in a new community which its Boston-based board of directors chose to name Claremont, “to indicate its clear mountain air and water”-or perhaps just with the thought of Claremont, New Hampshire, in mind. The company constructed a few homes and a spacious hotel for visitors. But after a few sales, the real estate market collapsed and Claremont appeared to be a town without a future. Meanwhile, in nearby Pomona, a fledgling college started by the Congregational Churches in Southern California was outgrowing its quarters but had not yet been able to build new facilities. The land company’s trustees offered Pomona College its vacant hotel and surrounding land at a bargain price and the college accepted.

Running out of room in the college’s one building, the faculty soon built their own homes and became the backbone of the community. Claremont, a California town set amongst sagebrush, oak trees, and artesian wells, quickly took on many of the characteristics of the New England towns that nurtured the small Eastern colleges which Pomona College hoped to emulate. Orange trees arrived in Claremont about the same time as the college. Together the citrus industry and the educational institution ensured the continued viability of the community, helped in the early 1900s by the arrival of electric railway service placing Claremont on a line between San Bernardino and Los Angeles.

Agricultural jobs for Mexicans and Asians added a bit of diversity to Claremont early in the twentieth century and a conscious decision to become a retirement community also had its influence. But the size and character of the city changed little until World War II. After the war, Claremont’s annual growth rate skyrocketed, peaking in 1960-1965 when the city was adding more than 1500 people per year. In 1954, the San Bernardino Freeway opened, furnishing an easy outlet to Los Angeles. At the same time, pollution and population growth contributed to the citrus industry’s decline. Residential and commercial uses for land now took precedence. Approaching the end of the twentieth century, the population of Claremont had become more diverse ethnically and occupationally, with many residents commuting daily to other parts of Southern California. Pomona College, having evolved into the cornerstone of a group of colleges, nevertheless remained a focal point of the community.

The Native Americans who wandered the lands near present-day Claremont were called the “Serrano” Indians after the Spanish term meaning “mountaineer, highlander.” In particular, they are known to have lived for a time on the mesa known as Indian Hill. A nomadic people, they normally settled near water and no doubt found the branch of San Antonio Creek and the artesian springs nearby to be good sources of water. Living in circular, domed brush homes, they ate acorns and hunted rabbits, deer, and bear in the bog and mountains in the vicinity. The Spanish forced the Serrano from their lands in the early 1800s, and they found themselves with few options other than working for the ranchers who took up residence in the area. In 1862 and 1873, smallpox epidemics ravaged the local Indian population and those few who survived had abandoned Indian Hill by the mid 1880s.

Historical photographs of the Claremont area can be found at the Claremont Heritage Historical Society and the Honnold Library of the Claremont Colleges.

Claremont Heritage Historical Society

590 W. Bonita Avenue

Claremont, CA 91711

(909) 621-0848

Honnold Library

747 Dartmouth Avenue

Claremont, CA 91711

(909) 621-8045

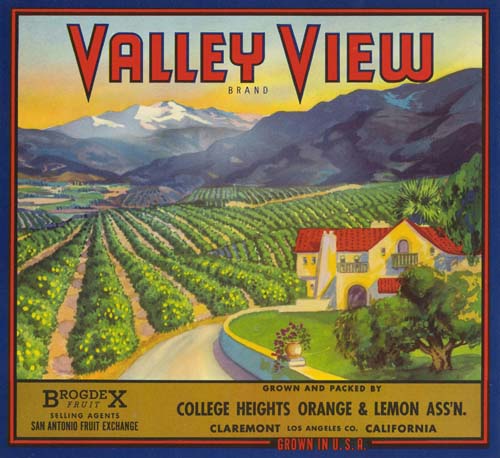

In 1888, Peter J. Dreher planted the first orange trees in Claremont. Four years later, he was marketing some three hundred boxes of oranges annually. Possessing very little experience growing oranges and facing high packing and shipping costs, Dreher teamed up with other area growers to establish the Claremont California Fruit Growers Association. Under the direction of the association, oranges were carefully graded and packed, with close attention to the quality of the fruit chosen for shipping. The efforts of the Claremont association, along with those of a similar association in Riverside, represented the start of the California Sunkist marketing system.

Meanwhile, the citrus industry became one of the bulwarks of the community. Claremont was a fine area for growing citrus, with plenty of water nearby, a good climate, and proper soil (once the many rocks in the ground had been cleared). By 1900, orange, lemon, and grapefruit groves crowded the countryside around Claremont. At one time, there were four packing houses and an ice and pre-cooling plant clustered around Claremont’s railroad tracks. Inside, workers, mostly immigrants and often women, sorted and graded the fruit. To arrange for a sufficient supply of water for the trees, the town’s citrus growers created cooperative water companies. Prospering for more than fifty years, the citrus industry lost its importance in the aftermath of World War II as residential homes and commercial development swallowed the former citrus groves.

After a brief sojourn in nearby Pomona, Pomona College, a small liberal arts institution established by the Congregational Churches of Southern California, moved permanently to Claremont in 1888. In the early 1920s, the college was flourishing and some believed it should expand to accommodate more students. Its president, Dr. James A. Blaisdell, argued against the idea of creating “one great undifferentiated university” and hoped instead to develop a system along the lines of that used by Oxford and Cambridge in England, that is “a group of institutions divided into small colleges . . . around a library and other utilities which they would use in common.”

In 1925, the Claremont Colleges were incorporated. In the years that followed, a handful of new colleges sprang up. Scripps College, a liberal arts school for women, opened its doors in 1926 using seed money from Ellen Browning Scripps. The end of World War II and the subsequent GI Bill spurred the creation of the Claremont Men’s College in 1946, with a focus on business, public administration, and training for other professional careers. The college first admitted women in 1976 and since 1981 has been known as Claremont McKenna College.

As Southern California became more industry-oriented, Harvey Seeley Mudd pushed for the establishment of a college devoted to science and engineering. In 1955, just after he died, Harvey Mudd College began operations, welcoming men and women with an interest in the sciences and engineering. In 1963, the state’s quickly growing population and the relative scarcity of women at the Claremont Colleges (there were roughly 700 more men than women enrolled at the time) prompted the establishment of a second women’s institution, Pitzer College, with special emphasis on the social and behavioral sciences. The College began in 1964 with an entering class of 153 students. Pitzer College began admitting men in 1970.

Since 1925, the Claremont Colleges have also included a small graduate school. While operating as independent academic centers, all of the institutions share such facilities as a library, auditorium, and medical center. In addition, the Claremont Colleges maintain relations with five affiliated institutions in Claremont: the Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, School of Theology at Claremont, Francis Bacon Library, Thomas Rivera Center, and Robert J. Bernard Field Station.